Facial recognition technology is a biometric technology that uses an automated process to identify individual people. It is used by law enforcement to identify suspects; at the border and in airports to facilitate travel and protect the homeland; and by a variety of private-sector businesses. It has the potential to increase people’s security and add convenience to their daily lives. It also has potential for abuse by both government and the private sector. Some observers have questioned whether the technology is accurate enough to be used in law enforcement decisions. Facial recognition technology remains largely unregulated in the U.S. and across the world.

Facial recognition is an example of biometric identification, like the use of fingerprints, eyes, voice, and other personal characteristics that cannot be easily imitated or changed. Of all the biometric identification techniques, it most closely mimics how humans identify each other: by recognizing their face. Facial recognition technology results are probabilistic, meaning they do not give a yes or no answer, but instead generate a likelihood of match.

Facial recognition systems can be used for a variety of functions including identifying a face in an image; estimating characteristics such as gender, race, and age; verifying identity; and identifying someone by matching an image of an unknown person to a gallery of known images.

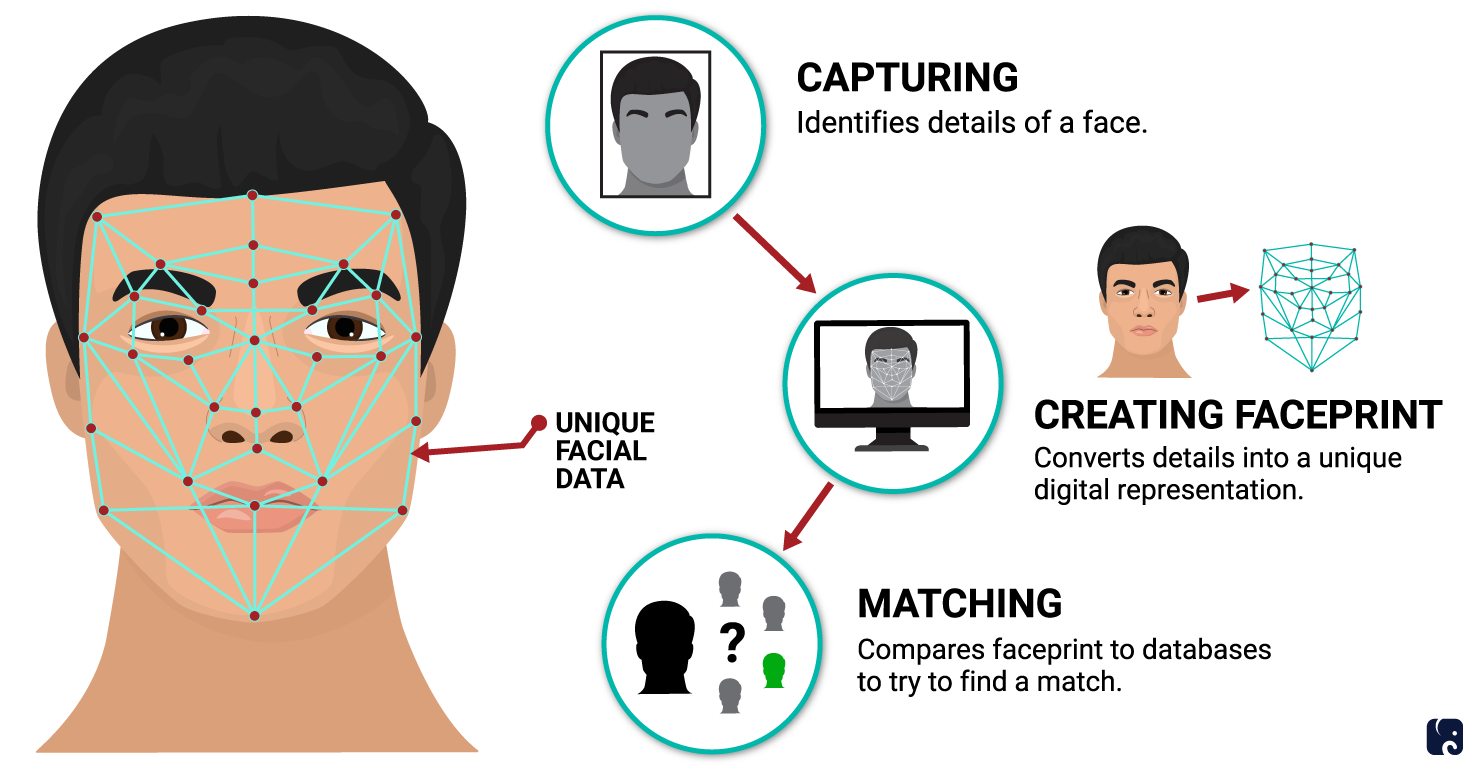

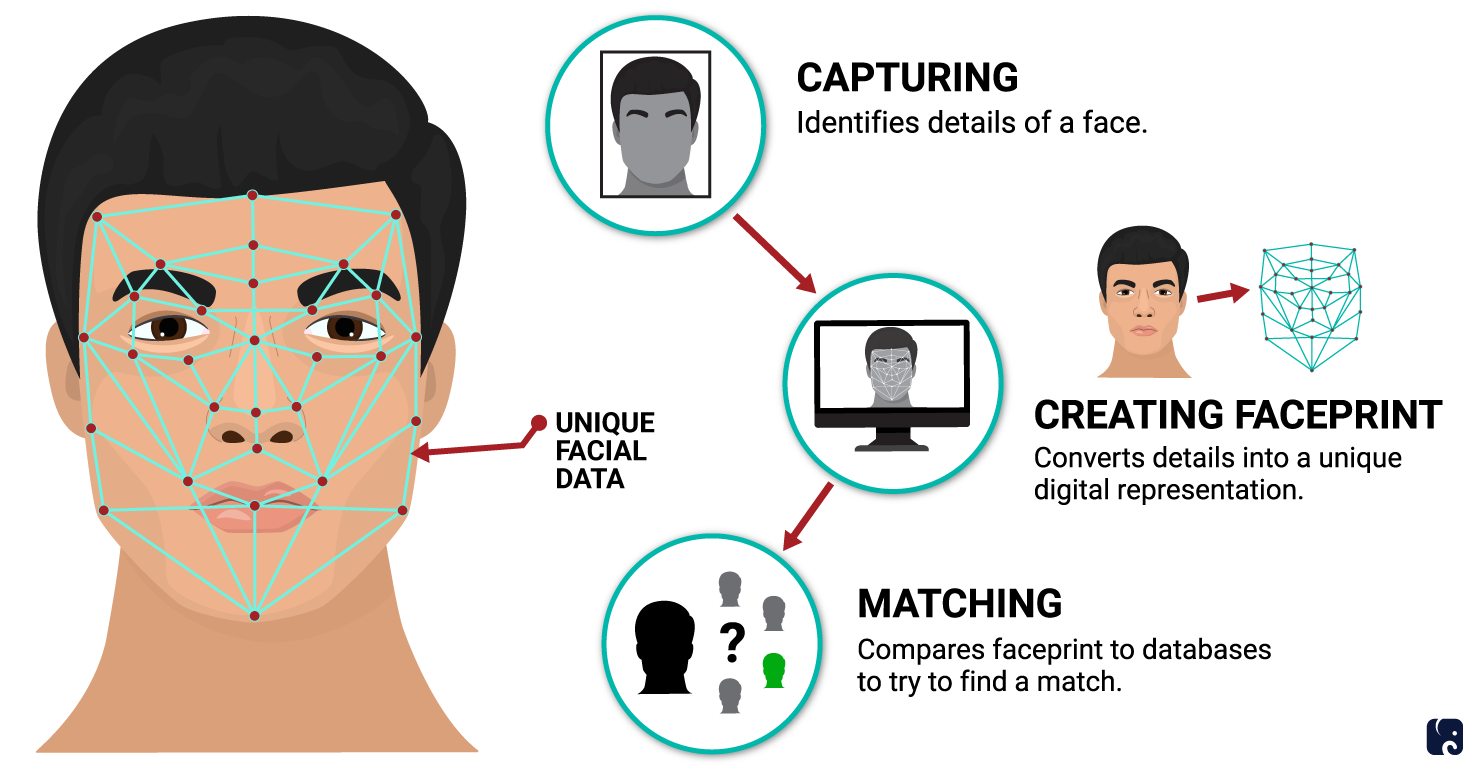

Several companies have developed their own facial recognition systems. Most of them use three main components: a camera; a database of stored images; and an algorithm that creates a “faceprint” from images captured by the camera to compare with the database images. Each of these components influences the accuracy of the facial recognition system. Some other systems are simply software that sorts or matches photos.

Facial recognition algorithms identify distinctive details about a face, such as distance between the eyes, and convert them into a digital representation, often referred to as a faceprint. Each system will measure slightly different aspects of a face and use its own proprietary algorithm to try to create the most accurate faceprint it can. The algorithm then compares the faceprint to a database of known faces to try to find a match.

The National Institute of Standards and Technology has measured the performance of companies’ facial recognition algorithms since 1993 and has found that the technology has improved over time. With high-quality images, the top algorithms tested in 2018 had an error rate of just 0.2% of searches. That is 20 times better than the best system the agency tested in 2013.

Research suggests that facial recognition may be disproportionately inaccurate when used on certain groups, including people with darker skin, women, and young people. Reasons for this may range from the way the light refracts off the skin to possible racial and gender biases in the data sets used to train facial recognition algorithms.

One study analyzed facial recognition technology from three major companies and found gender was misidentified only 1% of the time in the case of light-skinned men, but misidentified up to 35% of the time in darker-skinned women. A test of Amazon’s facial recognition system by the ACLU last year found it falsely matched 28 members of Congress to a database of mugshots. According to the ACLU, 20% of members of Congress are people of color, but they accounted for 39% of the false matches in its test. Amazon pushed back on the test results, noting that the study counted a “match” if the program found as little as an 80% chance the two images corresponded – far less than the 99% threshold the company recommends for law enforcement use. The company says that when it re-ran the test against a larger database and at the higher confidence requirement, it got a misidentification rate of 0%.

There are some concerns that law enforcement may be more likely to use the technology against people of color. As Rep. Elijah Cummings stated at a hearing in 2017: “If you’re black, you’re more likely to be subjected to this technology. And the technology is more likely to be wrong. That’s a hell of a combination, especially when you’re talking about subjecting someone to the criminal justice system.”

Facial recognition technology also raises constitutional issues. Depending on how the technology is deployed, it potentially could impact First, Fourth, and Fourteenth Amendment rights. Deployed at scale, it enables government agencies to use biometric surveillance remotely and in secret. Some experts have argued that such large-scale, constant, public surveillance would violate the Fourth Amendment. Others counter that people have no expectation of privacy in public spaces.

Law enforcement agencies at all levels have embraced facial recognition technology. The technology helps law enforcement identify criminal suspects, identify and rescue human trafficking victims, and secure the border. At least one in four state or local police departments is able to run facial recognition searches. Law enforcement officers use mobile devices and apps to capture images of people they interact with and identify them. Future versions of the technology may work in real time and in the dark.

According to a report by Georgetown law school’s Center on Privacy and Technology, one in two American adults is in a law enforcement facial recognition network. The FBI has access to 411 million photos, drawing from driver’s licenses, mugshots, and passport and visa applications. The Government Accountability Office has criticized the FBI for not conducting more thorough assessments of the accuracy of its facial recognition searches.

The Transportation Security Administration is evaluating the use of facial recognition technology to automate the identity and boarding-pass verification process at airport checkpoints. U.S. Customs and Border Protection uses facial recognition to process people at customs and border checkpoints. The FBI and Immigration and Customs Enforcement have reportedly used the technology to scan state driver’s license databases.

The military utilizes facial recognition technology to identify and vet suspicious people overseas. The Army is working to deploy real-time facial recognition body cameras that operate in all light conditions. The goal is for soldiers to quickly identify threats or persons of interest, such as people on a terrorism watch list. The special operations forces who conducted the raid that resulted in the death of former ISIS leader Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi reportedly used facial recognition technology to help quickly and positively identify the remains.

Some U.S. cities also are using the technology for law enforcement and public safety purposes. Detroit is reportedly operating a real-time video feed facial recognition system. And the Chicago Police Department reportedly has had access to facial recognition surveillance capabilities since at least 2016.

Retailers, casinos, financial institutions, apartment buildings and other private-sector businesses are using facial recognition to identify customers, prevent fraud and theft, and authorize entry into rooms and buildings. Facial recognition also is used to secure access to digital media; open or enable smartphones and other hardware; and record time and attendance in the workplace.

Most major U.S. airlines employ facial recognition technologies in their boarding processes. The technology has been used to help provide banking services in emerging markets, concert and ticketing services, and security at large sporting events.

Microsoft, which develops facial recognition technology, has publicly called for legislation and government regulation on the technology.

The authoritarian government in China has made wide use of facial recognition. The technology is reportedly one of China’s tools in its ongoing suppression of Uighurs, with the government even installing cameras in some people’s homes.

China will have an estimated 300 million cameras installed throughout the country by 2020, and has used facial recognition to identify protestors in its ongoing conflict with Hong Kong. Many protestors have donned masks in order to evade detection by the technology.

The United States does not have a comprehensive law governing the use of facial recognition by either private sector or government entities. However, some local bodies have moved forward with legislation and regulation. In addition, the Supreme Court has issued two Fourth Amendment cases that have relevance to facial recognition surveillance technology deployed in public.

In a landmark Fourth Amendment case decided in 2012, the court held that installing a GPS tracking device on a vehicle, and using it to track the vehicle’s movements for an extended period of time, constituted a search under the Fourth Amendment. Justice Alito noted in a concurrence that “society’s expectation has been that law enforcement agents and others would not – and indeed, in the main, simply could not – secretly monitor and catalogue every single movement of an individual” over a long period of time.

In a 2018 decision, the court held that accessing historical cell phone records for purposes of obtaining the geolocation of the device constituted a search under the Fourth Amendment, and accessing them requires a probable-cause search warrant. The Court stated: “A person does not surrender all Fourth Amendment protection by venturing into the public sphere.” Justice Alito, in a dissent suggested Congress was the better place to have this debate: “Legislation is much preferable to the development of an entirely new body of Fourth Amendment caselaw for many reasons, including the enormous complexity of the subject, the need to respond to rapidly changing technology, and the Fourth Amendment’s limited scope.”

Three states – Texas, Illinois, and Washington – have adopted biometric privacy laws that govern the commercial use of biometric identifiers, including those used by facial recognition technology. In May, San Francisco became the first U.S. city to ban the use of facial recognition surveillance by city agencies, including the police department. Oakland and other surrounding cities soon followed suit.

Congress has held hearings and lawmakers have introduced legislation related to facial recognition technology. The House Oversight Committee held two hearings on the issue this year, where members expressed bipartisan support for congressional action. Senators Roy Blunt and Brian Schatz have proposed bipartisan legislation that would require business to obtain consumers’ consent before using facial recognition technology. And Senators Chris Coons and Mike Lee have proposed bipartisan legislation that would require law enforcement to obtain a probable-cause search warrant to use facial recognition technology for ongoing surveillance of a person.

The European Union is considering significantly tightening EU regulations and restrictions on the use of facial recognition technology.