Cultural and linguistic diversity is a core feature of the Australian population and a valued element of national identity. The proportion of the population that will be overseas-born is projected to be 32% by 2050. While a very active process of mental health system reform has been occurring for more than two decades - at national and state and territory levels - the challenges presented by cultural and linguistic diversity have not been effectively met. A key area in which this is particularly an issue is in the collection, analysis and reporting of mental health data that reflect the reality of population diversity. The purpose of this study was to examine: what is known about the mental health of immigrant and refugee communities in Australia; whether Australian mental health research pays adequate attention to the fact of cultural and linguistic diversity in the Australian population; and whether national mental health data collections support evidence-informed mental health policy and practice and mental health reform in multicultural Australia.

The study consisted of three components – a brief review of what is known about mental health in, and mental health service use by, immigrant and refugee communities; an examination of national data collections to determine the extent to which relevant cultural variables are included in the collections; and an examination of Australian research to determine the extent to which immigrant and refugee communities are included as participants in such research.

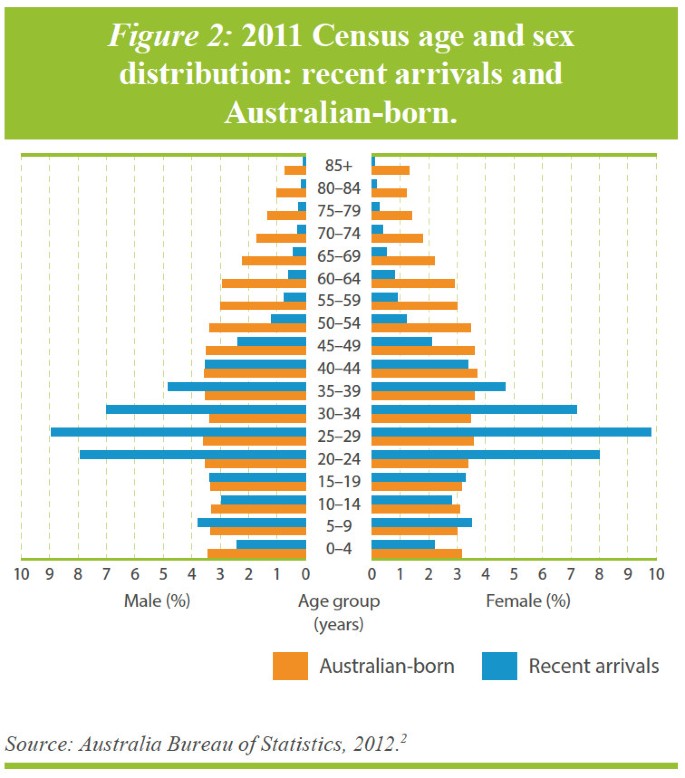

The review of Australian research on mental health of immigrant and refugee communities and their patterns of mental health service use generated findings that are highly variable. The work is fragmented and usually small-scale. There are multiple studies of some immigrant and refugee communities and there are no studies of others. Although there is a broadly consistent pattern of lower rates of utilisation of specialist public mental health services by immigrants and refugees the absence of adequate population epidemiological data prevents judgments about whether the observed patterns constitute under-utilisation. There are virtually no data on quality of service outcomes. The examination of national data collections revealed multiple gaps in these data collections. The review of papers published in four key Australian journals to determine whether immigrants and refugees are included in mental health research studies revealed a high rate (9.1%) of specific exclusion from studies (usually due to low English fluency) and a much higher rate of general neglect of the issue of population diversity in study design and reporting.

While there are many positive statements of policy intent in relation to immigrant and refugee communities in national mental health policies and strategies there is virtually no reporting by Commonwealth or State and Territory governments of whether policies that are relevant to immigrant and refugee communities are effectively implemented. It is not possible, on the basis of the data collected, to determine whether immigrant and refugee communities are benefiting from the mental health system reforms that are being actively carried out. The majority of Australian mental health research does not adequately include immigrant and refugee samples. On the basis of the findings of this study eight strategies have been recommended that will contribute to the development of a culture of inclusion of all Australians in the national mental health research enterprise.

All people have certain fundamental human rights. Membership in our society confers on all Australian residents, including people with mental health problems or mental disorders, certain rights, roles and responsibilities. Australia is a diverse society comprising people from a wide variety of cultural and linguistic backgrounds. Every Australian needs to be encouraged to maintain his or her mental health and to work towards the prevention of mental health problems and mental disorders. Some may require assistance to do this. The Commonwealth, State and Territory Governments are now seeking to redress inequities in Australian society by way of social justice strategies[1].

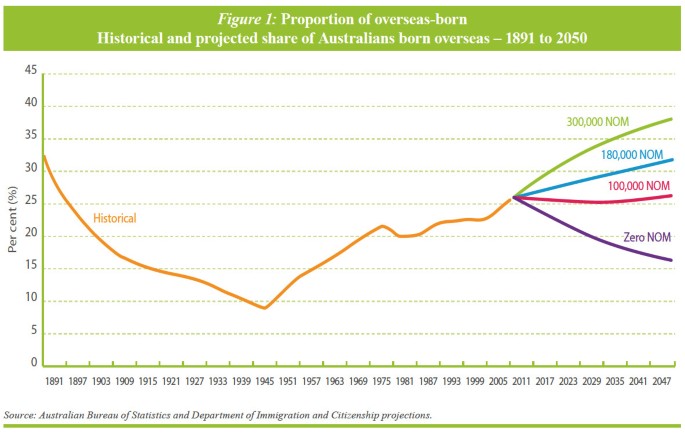

Cultural and linguistic diversity is a core feature of the Australian population [2] and a valued element of national identity. If net overseas migration continues at the current rate the overseas-born component of the Australian population will increase from the current proportion of more than 25% to around 32% in 2050 [3]. The existing cultural and linguistic diversity of the population, and the arrival of immigrants and refugees from a very wide range of source countries [2] will continue to present challenges for all forms of service delivery, including mental health services, into the foreseeable future.

The process of mental health system reform has been occurring in all States and Territories since the 1950s. The development of a National Mental Health Strategy in 1992 [4], endorsed by the Commonwealth and all State and Territory governments, has given considerable impetus to the reform process. There has been a major shift from hospital to community-based service delivery [5], substantial increases in the mental health workforce, improved access to mental health services in primary care, improved mental health literacy in the general population [6], substantial increases in participation in decision-making by people with mental illness and their families and support persons [7], and a continuing move from a focus on medical treatment to recovery-oriented mental health [8, 9] and psychosocial support services.

Key components of the national reform process have been a clear statement of rights and responsibilities [1], the development of national standards for service delivery [9], a commitment to evidence-informed policy development, service delivery and reporting of progress against policy intent [7], and a focus on service outcomes [10]. In all relevant Commonwealth, State and Territory mental health policy documents culturally and linguistically diverse (CALD) populations have been identified as warranting particular attention in order to ensure equity [11].

However, it is not clear whether immigrant and refugee communities - particularly those who do not speak English, the most recently arrived and refugees, who are among the most vulnerable – have benefited from this process of major mental health system reform.

The collection and analysis of mental health data is central to moving toward equity in mental health. Without data on the population distribution of mental health and mental illness, the patterns of service use by different sections of the population, and the quality of outcomes of health service contact, unjust inequalities remain invisible. Mental health and mental health service inequities need to be made visible to enable evidence-informed policy development, mental health service design and delivery, and clinical and recovery practice. Comprehensive and reliable data are essential to evaluate the degree to which policies and programs enhance equity, provide direction for research into root causes, and guide new strategies for promoting health [12].

The purpose of this study is to examine:

The recommendations, based on the main findings, are intended to contribute to the development of a culture of inclusion of all Australians in the national mental health research enterprise.

“Whatever the future holds for Australia, history suggests it will be inextricably bound up with immigration.”[13]

The cultural and linguistic diversity of the Australian population has been shaped by Australia’s unique history. At the end of World War II, the population was approximately seven million, of whom 10% were overseas-born [14]. Since the end of the Second World War the proportion of overseas-born has steadily increased [3]. (Figure 1) The first post-war wave of migration consisted predominantly of new arrivals from Europe [14]. In each of the subsequent decades, an additional one million immigrants arrived [14]. By June 2011, the population was 22.3 million of whom 26% were born overseas and an additional 20% had at least one overseas-born parent [2]. Over the past ten years, the overseas-born population has increased by 23.1% [15].

In 2011 persons born in the United Kingdom continued to be the largest country-of-birth group (5.3% of the total population), followed by people born in New Zealand (2.5%), China (1.8%), India (1.5%), Vietnam (0.9%) and Italy (0.9%) [2].

Migration source countries have continued to change, with a reduction in migration from the United Kingdom and significant increases in migration from New Zealand, China and India. The most rapid population growth between 2001 and 2011 was for persons born in Nepal (with an average annual increase of 27%), Sudan (17.6%), India (12.7%), Bangladesh (11.9%) and Pakistan (10.2%) [15].

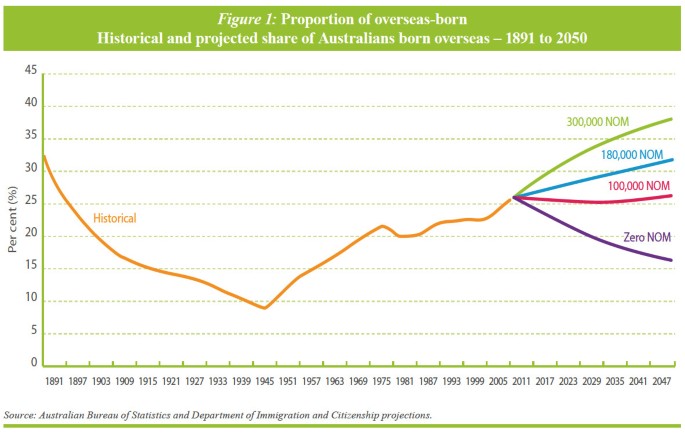

Recent immigrants are younger than the general population [2] (Figure 2) while longer-standing immigrants are older than the general Australian population (Figure 3) [2]. The relative youth of recent arrivals is important for mental health. Adolescence and young adulthood is the peak period of onset of most mental disorders. This is also a period for many immigrants when they are dealing with the many stresses associated with migration and settlement. For longer-settled immigrants the key issue is the mental disorders of old age. Disorders associated with cognitive impairment are a substantial challenge for families and for the mental health system, particularly when they include deterioration in the person’s capacity to communicate in English.

The majority of recent immigrants (67%) and almost half (49%) of the longer-standing immigrants speak a language other than English at home [2]. For longer-settled immigrants, Mandarin (4.3%), Cantonese (4.2%), Italian (3.7%) and Vietnamese (3.2%) were the most common languages spoken at home other than English, while for recent immigrants, Mandarin (10.8%), Punjabi (3.7%), Hindi (3.3%) and Arabic (3.0%) were the languages other than English most frequently spoken at home [2].

Approximately half (51%) of the longer-settled immigrants reported that they could speak English very well, while only 2.6% reported that they could not speak English at all. Among recent arrivals (past 10 years) 43% reported that they speak English very well, while 3.1% reported not speaking English at all [2]. There is, as expected, wide variation in level of English fluency among country-of-birth groups.

While cultural and linguistic diversity represents a significant challenge, the development of mental health services that are responsive, accessible, culturally appropriate and effective in meeting the needs of people with mental illness and their families and support persons, is not a distraction from the’ core business’ of mental health services. Working through the process of reforming services so that they are capable of meeting the needs of a culturally diverse society will have the direct benefit of making those services more flexible and responsive to the needs of all members of the Australian community.

Our community is rich in diversity. It embraces cultural and religious differences. This brings many strengths and opportunities, but we also need to recognise the challenges faced at times by some within our community. There should be demonstrated cultural competency in the planning and delivery of responsive mental health services[16].

An analysis of Commonwealth, State and Territory mental health policies, and of specific transcultural mental health policies developed in New South Wales, Queensland, Victoria, and Western Australia, revealed that statements such as the above are common [11]. Commonwealth, State and Territory mental health policies were examined for their relevance to mental health system responses to depression in immigrant and refugee communities. Specialised State ‘transcultural mental health’ policies provided comprehensive policy coverage of issues relevant to mental health and immigrant and refugee communities. Key topics were identified from these transcultural mental health policies and used to analyse each of the general Commonwealth, and State and Territory mental health policies. There was a highly variable degree of attention to issues relevant to immigrant and refugee communities. Commonwealth policies contained a relatively comprehensive coverage of issues. Areas that were unrepresented or under-represented included: providing information which supports access; interpreters/language services; coordination of care; support for ethnic community workers; data collection; and service utilisation. More recent policies tended to include a clearer focus on immigrant and refugee communities and highlighted the need for improvement in the evidence base for all forms of mental health activity in relation to immigrant and refugee communities. Policies developed have tended to repeat the same aspirations concerning immigrant and refugee communities, as illustrated by the quote above from the 4th National Mental Health Plan [16].

While such statements of policy intent are a welcome acknowledgement of the need to focus on cultural and linguistic diversity, two key questions remain. To what extent are such statements of policy intent included in policy implementation plans or used to establish funded programs? Do Commonwealth, State and Territory governments and mental health service agencies report progress against such statements of policy intent?

A survey seeking information on whether services were addressing depression in immigrant and refugee communities was sent to 1,480 organisations in capital cities and major regional towns across Australia [11]. The organisations surveyed included mental and general health service providers, Divisions of General Practice, public health units, Local Governments, Migrant Resource Centres, transcultural mental health services, refugee services and ethnic community organisations. Relevant programs were analysed in relation to reported strategies and activities, barriers, supports, perceived role in relation to depression in immigrant communities, partnerships, and program involvement of immigrant communities, people with mental illness and their families and support persons. From the 1,480 organisations to which questionnaires were sent 422 organisations (28%) responded to the survey. A total of 46 programs were identified that specifically addressed mental health in immigrant and refugee communities and a further eight programs reported that they were mainstream mental health programs that had made some adaptation to be more responsive to the needs of immigrant and refugee communities. “Direct clinical services, such as counseling, psychotherapy, psychiatric case management, psychological rehabilitation, day activity programs, self-help and mutual support groups for those with mental disorders, were all reported by mainstream mental health organisations. These were regarded as available to the whole of the community with no particular adaptations of programs to accommodate the varied needs of ethnic minority communities” [11].

The continuing process of mental health system reform in Australia, particularly over the past two decades, has resulted in major changes in the ways in which professionals and communities think about mental health and illness, in the ways in which mental health services are designed and delivered, and in the level of priority accorded to mental health by Commonwealth, State and Territory governments. The general population is more knowledgeable about mental health and illness [6] and more likely to seek mental health treatment and care [5], services are much more community-focused, the importance of primary care in service delivery has been recognised and supported, participation of people with mental illness and their families and support persons in decision-making has been considerably strengthened, and there has been a strong and deliberate move to recovery-oriented service delivery. While these achievements have led to Australia being regarded as a world leader in mental health system reform, it is recognised that there is still much to be done [17].

It is clear that policy-makers are aware of the relevance of cultural and linguistic diversity and of the need to take such diversity into account when framing mental health policy, and when designing mental health services. However, there is very little implementation of those components of mental health policies that relate to the particular needs of immigrant and refugee communities.

Lack of implementation is all but invisible because reports of progress in implementation of Commonwealth, State and Territory mental health policies generally say nothing about immigrant and refugee communities. A recent and important example is the National Mental Health Report 2010 [7]. The report “summarises the progress of mental health reform undertaken over the fifteen years of the National Mental Health Strategy, and provides a view of trends and performance at the national and State and Territory levels over the period spanning the First, Second and Third Mental Health Plans from 1993 to 2008.” This Summary of 15 Years of reform in Australia’s Mental Health Services under the National Mental Health Strategy 1993–2008, like the ten National Mental Health Reports that preceded it, has nothing to say about immigrant and refugee communities.

As a result of such neglect, and exclusion from implementation and reporting processes, there may well be persistent disparities in availability of and access to mental health services, quality of care, and mental health outcomes for people from immigrant and refugee backgrounds [18–22]. The lack of comprehensive and reliable data on mental health of immigrant and refugee communities means that disparities and inequities that do exist are all but invisible.

“As a group, people born overseas have health characteristics that are different from the rest of the population. The mortality and morbidity patterns of migrants can be influenced by both their country of origin and where they currently live, and by the process of migration itself.”[23]

What is known about mental health of immigrant and refugee communities in Australia and what are the major gaps in our knowledge? To answer this question a search of publications reporting mental health research carried out in Australia between 1963 and August 2012 was carried out to identify studies that included immigrant or refugee communities and that focused on immigrant and refugee mental health issues. The search yielded 214 original research articles reporting findings on mental health issues from samples of participants from immigrant and refugee background. The findings below are from this review.

Knowledge of prevalence of mental disorders is essential for several reasons. Without reliable estimates of prevalence of different types of mental disorders in CALD communities it is impossible to say anything about the scale of mental health problems in different populations. It difficult to evaluate whether attempts to improve population mental health are effective and a good investment. It is also difficult to determine whether differences in rates of service utilisation by those sub-groups are due to differences in prevalence or due to other factors, such as obstacles to service access. Reliable prevalence estimates are important to inform mental health policy and service design and delivery.

The National Survey of Mental Health and Wellbeing conducted by the Australian Bureau of Statistics [5] provides the best available estimate of the prevalence of mental disorders across Australia. Information from the survey is very important in formulating government mental health policies and decisions about mental health services.

The 2007 National Survey of Mental Health and Wellbeing collected information from 8,841 Australians aged 16–85 years. The survey provides information on the prevalence of selected mental disorders (Anxiety, Affective, and Substance Use disorders), sex and age distributions, comorbidity, and the extent of impairment of core activities and health service utilisation.

Demographic characteristics relevant to people from immigrant and refugee backgrounds included: Country of Birth, Year of Arrival, Country of birth of mother or father, and Proficiency in spoken English. The classification of countries used is the Standard Australian Classification of Countries (SACC).

While the Australian Bureau of Statistics provides an overview of the findings from the survey [5] most of the detailed analyses that are available have been carried out by researchers with access to the survey dataset [2, 10, 19, 21, 24–39]. None of these studies has analysed findings relevant to immigrant and refugee participants in the survey. (There was one study examining access to mental health care by people from non-English-speaking background using data from the first, 1997, National Survey of Mental Health and Wellbeing [40]).

The results relevant to immigrant and refugee participants reported from the 2007 national survey are prevalence rates by country of birth (Australia or Overseas) and year of arrival of immigrants. Respondents born outside Australia were found to have lower prevalence of anxiety, affective, substance use disorder, and of any 12-month mental disorder [5] (Table 1). Those most recently arrived (in the decade prior to the survey) have the lowest rates of disorder.

The great majority of papers made no mention of cultural and linguistic diversity of the populations that were being sampled and studied. In 2.9% of studies there was some general mention, but no specific analysis, of CALD issues or populations, and in 9.7% of studies there was specific consideration of CALD issues or inclusion of CALD samples. In 9.1% of studies the exclusion criteria for sampling and participation included insufficient proficiency in English.

Gathering evidence… requires that greater priority be given to innovative mental health research in a range of fields, including the biomedical, psychological and social sciences, program evaluation and health economics. At present, there is limited evidence as to how best to tailor assessment and treatment for specific populations, including Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples and people from culturally diverse backgrounds[1].

In this section we briefly examine approaches taken by three countries – Canada, UK and USA – to ensure inclusion of minorities in their respective national research efforts. The historical and cultural similarities of these countries to Australia are self-evident. They are all countries with formal and long-term immigration programs, have multicultural and multilingual populations and face similar challenges in provision of effective and appropriate health and mental health services to CALD populations.

It is clear that other similar countries with multicultural populations have developed disparate strategies that aim to ensure that minority populations are included as much as possible in clinical and population mental health research. Several of the strategies, with appropriate modification, may be applicable in Australia.

Federal agencies are required to take positive measures to ensure the support and recognition of minority language communities in Canada which, for the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (CIHR), means an obligation to promote health research that includes these communities [141]. In 2003 the House of Commons Standing Committee reported the difficulties that Official Language Minority Communities (OLMCs) experienced in accessing health services in their language of choice, and that the insufficient empirical evidence on the challenges faced by both French-speaking and English-speaking minority communities was a main barrier to the development of strategies for improving access to health services in both official languages. This led to processes designed to identify the needs for and gaps in research on the health of OLMCs and strategies for increasing the number of researchers in the field.

The outcome was a CIHR Strategic Research Initiative on OLMCs. The initiative aimed to: (1) promote the study of health determinants and specific needs of the French and English-speaking minority communities; (2) increase the number of researchers taking an interest in these issues; and (3) ensure that newly created knowledge is transmitted to researchers, clinicians and other stakeholders, with the view of improving the health of Canadian populations [142].

In Canada, a longitudinal National Population Health Survey (NPHS) household component was created to gather information about the health of general population [143] and is conducted every two years, in one of a choice of 23 languages. This survey started in 1994 (cycle 1). The most recent cycle (cycle 9) was performed in 2011. In each cycle, a common set of health questions is asked to the respondents. It includes questions about mental health and well-being, disease and health status, nutrition, health care utilisation, as well as lifestyle and socio-economic conditions. Based on the most recent questionnaire [144], respondents were able to complete the survey interview - either by telephone or face-to-face - in one of the 23 main languages spoken in Canada.

In the United Kingdom, the anti-discrimination Equality Act of 2010 serves to protect the rights of all individuals in Britain and has a clear list of “protected characteristics” such as age, disability, gender reassignment, marriage and civil partnership, pregnancy and maternity, race, religion and belief, sex and sexual orientation [145]. Although it is not an explicit directive for inclusion of minorities in research the Act does apply to a number of regulatory bodies which may engage in research activities including government departments, service providers, employers and education providers.

The National Health Service in the UK has acknowledged the importance of inclusion of “black and minority ethnic” (BME) communities [146]. It is recognised that these communities have poorer health outcomes, a shorter life expectancy and difficulty in obtaining access to health care with mental health being of particular concern [147]. A five-year action plan called the Delivering Race Equality in Mental Health (DRE) was established in 2005 with the goal of reducing inequalities for BME communities particularly in relation to their experience of and interaction with mental health services [148]. A review of the DRE identified a significant increase in the commissioning of research in these communities. According to the DRE their research has “helped us to improve ethnic monitoring, identify good practice and provide better information to patients” [148].

The Research Governance Framework for Health and Social Care [149] outlines the overarching principles of good research governance. Specifically the framework applies to research applicable to health and social care (i.e., including research relating to public health, research undertaken by the Department of Health, clinical and non-clinical research, the National Health Service (NHS) and other research bodies within the health and social care systems). According to the Framework [149]: ‘Research, and those pursuing it, should respect the diversity of human society and conditions and the multicultural nature of society. Whenever relevant, it should take account of age, disability, gender, sexual orientation, race, culture and religion in its design, undertaking, and reporting. The body of research evidence available to policy makers should reflect the diversity of the population.’

The UK has a mental health minimum dataset (MHMDS) [150] that is an approved National Health Service information standard. It was designed to deliver comprehensive, nationally consistent and comparable person-based information on people in contact with specialist secondary mental health services. It covers services provided in hospitals, outpatient clinics and in the community. The minimum dataset includes indicators of patients’ ethnicity. According to the fifth NHS Information Centre for Health and Social Care report [150] “Information on the ethnicity of people using services is now almost complete for people who spend time in hospital (97.4 per cent) and 89.5 per cent complete for people who did not spend time in hospital. This means that analysis by ethnic group is considered quite reliable”.

A national census of the ethnicity of inpatients in NHS and independent mental health and learning disability services in England and Wales has been conducted since 2005. The fifth report showed that information about ethnicity was available for 98% of all patients [151].

In the United States of America the National Institutes of Health (NIH) are mandated by law to ensure the inclusion of minority groups in clinical research. The inclusion of these minority groups in clinical research must be in a manner that is appropriate to the scientific question under study [152]. Minorities must be included in all clinical research studies, particularly in Phase III clinical trials, and the trials must be designed to allow valid analysis. The law explicitly states that cost is not acceptable as a reason for exclusion of minority populations. Clinical research applications that fail to include minorities without providing a valid reason may be returned without review.

Women and minorities may only be excluded if inclusion in a clinical research study is:

Since 1994 NIH has continuously monitored aggregate inclusion data for study populations through a tracking system to ensure compliance with the inclusion policy. In 2002 NIH changed the format of data reporting from combined race and ethnicity format to collecting and reporting information on race and ethnicity separately [154]. This provided minimum standards for maintaining, collecting and reporting data on race and ethnicity.

The consumer has the right to have services subjected to quality assurance to identify inadequacies and to ensure standards are met[1].

Improvement of national data collections… will be critical to the design and refinement of services and supports, and to the identification of service gaps[155].

There are many positive statements of policy intent in relation to immigrant and refugee communities in national mental health policies and strategies - in the Statement of Rights and Responsibilities, in the National Mental Health Standards, in multiple State and Territory policies and mental health plans, and recently in the COAG Roadmap for National Mental Health Reform.

However, there is virtually no reporting by Commonwealth or State and Territory governments concerning implementation of policy intent in relation to immigrant and refugee communities or evaluation of implementation. It is not possible to determine whether there has been any improvement in immigrant and refugee community mental health, access to mental health services or outcomes of contact with mental health services.

Investigator-initiated research on mental health of immigrant and refugee communities has yielded important insights into the mental health of particular immigrant and refugee communities, determinants of mental health and illness and patterns of use of mental health services. However this research is limited and does not provide a coherent account of the mental health of Australia’s CALD population. Nor does it answer critically important policy- and practice-relevant questions. An issue of particular importance in relation to CALD communities is the lack of systematic investigation and understanding of the perspectives and beliefs of families and carers concerning mental health and illness and mental health services, and the experience of members of CLD communities who come into contact with mental health services.

The most striking observation is the wide variation in findings across different immigrant and refugee communities. This variation represents a valuable and unrealised opportunity to systematically study population risk and protective factors for mental health and illness that would be of enormous theoretical and practical importance for the whole Australian population.

The majority of Australian mental health research does not adequately include immigrant and refugee samples. The number of studies that have specifically included adequate representative samples of immigrant and refugee populations or that have explicitly investigated multicultural mental health issues is very small. What we increasingly know about the mental health of the Australian-born population we do not know about immigrant and refugee communities.

The available evidence suggests that in, Australia, adult immigrants appear to have lower prevalence of mental illness than do the Australian-born. There is generally no difference reported in prevalence of mental disorders between immigrant and Australian-born children. It is not clear whether there is in fact a lower prevalence of mental disorders in immigrant and refugee communities or whether this conclusion is an artefact of the research methods used. Conclusions about the average prevalence of mental illness in overseas-born Australians may well be accurate, but the available data allows no conclusions to be drawn about prevalence in even the largest immigrant communities. The exclusion of immigrant and refugee participants, particularly non-English speaking persons, from national surveys and from individual epidemiological research projects does not allow any confident statement about prevalence of mental disorders in specific immigrant and refugee communities.

Factors contributing to increased risk of mental health problems in CALD populations include low proficiency in English, separate cultural identity, loss of close family bond, stresses of migration and adjustment to the new country, limited knowledge of the health system, trauma exposure before migration, and limited opportunity to appropriately use occupational skills. Factors that appear to be protective of mental health include religion, strong social support and better English proficiency. Studies that provide information about determinants have not been systematically examined to draw reliable conclusions concerning risk and protective factors for mental health and illness or about patterns of mental health service use.

Suicide rates in CALD populations generally reflect the rates in the country of birth. Suicidal behaviours in immigrants are associated with the problematic living experiences in the host country and in the country of origin. Strong family bonds, religion and traditional values were associated with lower suicide risk. The wide variations in suicide rates across immigrant and refugee communities represents a valuable and unrealised opportunity to systematically study population risk and protective factors that may find wide application in the development of more effective suicide prevention strategies for the Australian population.

Refugees and asylum seekers are at greater risk of developing mental health problems and suicidal behaviours than is the general Australian population. Prolonged detention has been found to be associated with poorer mental health in refugees and asylum seekers, particularly among children. Other factors influencing mental health of refugees and asylum seekers include experience of human rights violations, exposure to violence and threats, on-going temporary protection visas and experience of pre-migration trauma.

Generally, immigrants, refugees and asylum seekers have lower rates of mental health service utilisation than the Australian-born. The key barriers to access to mental health services in immigrants and refugees include greater stigma attached to mental illness and limited knowledge of mental health and services relative to Australian born. There is a general and persistent pattern of low rates of use by immigrant and refugee communities of specialist mental health services. Anecdotal evidence suggests that this is also the case in psychiatric disability and disability support services provided by mental health NGOs. In the absence of reliable prevalence data for CALD populations this observation is uninterpretable. It is not known whether the low utilisation rates are due to lower prevalence of mental disorders or whether system or community level barriers to mental health service access can explain them. This makes it impossible to determine whether the repeatedly stated policy intent of national, State and Territory mental health policies and plans concerning access to services and equity of service provision has been achieved.

The Council of Australian Governments (COAG) has acknowledged the general weakness of evidence for mental health system reform [155]. “There is a need to continue research and data development to improve our collective knowledge and understanding of mental health and wellbeing, the many factors contributing to it, their interaction, and effective ways to improve and maintain mental health for people across the population. For example, current Australian mental health and broader health data collections are inadequate in their description of the mental health and social and emotional wellbeing of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people.” Despite the identification throughout the Roadmap of the need for specific strategies to respond to the needs of people from culturally and linguistically backgrounds there is no similar acknowledgment of the deficiencies in data concerning immigrant and refugee populations [155]. Under the section title Monitoring the Journey the Roadmap states that “Where data is available, (emphasis added) they will consider outcomes and progress for different parts of the community, particularly Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people, as well as by factors such as age group, gender, language and cultural background, socioeconomic status and location (e.g. urban or remote areas).” The key finding of this paper is that in relation to immigrant and refugee communities the necessary data are not available.

The key findings are highlighted here and a recommendation is made in relation to each key finding.

Population projections are clear. Immigration, including a significantly increased humanitarian intake, will be a continuing major contributor to Australia’s future, as well as being a significant challenge to the provision of all kinds of human services, including mental health services.

Ensure that the increasing cultural and linguistic diversity of the Australian population is a core consideration in all mental health policy-making and funding for policy implementation of mental health service design, delivery and evaluation. This will require the full participation of representatives of immigrant and refugee communities and people with mental illness and their families and support persons in policy making and implementation processes.

Although attention to population diversity is a feature of most mental health policies policy statements are not translated into implementation objectives, funding is not made available to support implementation, and there is no adequate reporting of progress against policy intent in relation to immigrant and refugee communities.

Translate mental health policy statements that are relevant to CALD communities into explicit implementation objectives and identify funds and other resources that are needed to support implementation activities and programs that will achieve CALD mental health policy objectives, and report on progress on policy objectives in relation to immigrants and refugees.

Available research findings on prevalence of mental disorders in immigrant and refugee populations are incomplete and contradictory. There is no comprehensive Australian study of prevalence of mental disorders in immigrant and refugee populations that is adequate in scale and that enables valid disaggregation (e.g. by country of birth language or duration of residence groups) in the analysis of results. Future research that includes representative samples of at least some immigrant and refugee populations is required to address this issue.

The commonly reported observation that prevalence of mental disorders in refugee and asylum seeker communities is higher than that of the general Australian population is based on small-scale studies that often have methodological problems. Although there are many reasons to expect that prevalence in these groups will be higher larger, more comprehensive and methodologically rigorous studies are required before there can be confidence in the accuracy of the findings of higher prevalence.

Ensure that national surveys of mental health include representative samples of at least some non-English speaking background populations to improve population relevance of findings.

The evidence on determinants, explanatory models of illness, attitudes and beliefs concerning help-seeking and mental health services, is sparse, fragmented and based on small-scale studies of very few immigrant and refugee communities. A better understanding of determinants of mental health and illness in CALD populations, and of explanatory models of illness, beliefs and attitudes towards mental disorders and mental health services that includes the perspectives of family members, carers and support workers is a pre-condition for development of effective policy and effective mental health promotion and prevention, and mental health service programs.

Allocate high priority to research on the determinants of mental health and illness; explanatory models of mental illness; beliefs, knowledge and attitudes towards health services; and help-seeking among immigrant and refugee communities. This requires a particular focus on perspective and beliefs, and full involvement, of people with mental illness and their families and support persons in the investigation of the experience of members of CALD communities who have come into contact with mental health services.

There is quite good information on patterns of use of public specialist hospital and community mental health services. This research consistently shows that certain (particularly Asian) immigrant and refugee communities use mental health services at significantly lower rates than do the Australia-born. Although this is frequently reported as service ‘under-utilisation’ this interpretation of the observed patterns of mental health service use is not justifiable in the absence of reliable prevalence estimates and need-for-service data. Such data are required before judgments about whether utilisation rates are consistent with service needs.

Although there is a great deal of comment on probable reasons for underutilisation of mental health services by many immigrant and refugee communities there is very little research on the factors that influence patterns of services use. In particular there is little research on the influence of family and carer perspectives and beliefs, and prior experience of mental health services, on help-seeking and service access pathways.

There is virtually no data on immigrant and refugee community utilisation of mental health services provided through primary care, specialist private mental health services and psychiatric disability and rehabilitation support services.

Ensure adequate reporting of patterns of use of mental health services, and the experience of mental health services, of immigrant and refugee communities as part of the national mental health policy reporting framework.

While investigator-initiated research has provided valuable information on many aspects of the mental health of immigrant and refugee communities it has not provided answers to questions that are of most importance to policy-makers, service designers, managers, evaluators and practitioners. Although investigator-initiated research is an essential component of any research enterprise, and must continue to be encouraged and supported, it should be complemented by a program of strategic policy- and practice-relevant multicultural mental health research to deal with the fact that immigrant and refugee communities are effectively excluded from the national mental health research and evaluation enterprise. The impact of this exclusion is that there are large and persisting gaps in knowledge about mental health of immigrant and refugee communities. Closing these gaps will require a systematic and targeted approach.

Develop a multicultural mental health research agenda that will serve as a guide to researchers, research students and research funders concerning high priority, policy- and practice-relevant research. Immigrant and refugee communities and people with mental illness and their families and support persons should be fully involved in the development of such a research agenda.

The systematic absence of key CALD variables from virtually all Commonwealth, State and Territory funded data collections is a clear indication of the low national priority that is accorded to the mental health of Australia’s immigrant and refugee communities. This absence, or exclusion, ensures that what we increasingly know about the mental health of the general community, and the effectiveness of mental health services for the general community, we systematically do not know about immigrant and refugee communities, particular those among them who do not speak fluent English. The failure to collect CALD-relevant data as part of the national program of outcomes data collection is one of the most important and glaring gaps in CALD mental health data collections. This makes it impossible to evaluate the effectiveness of mental health services received by immigrant and refugee communities, care utilisation and continuity of care.

Ensure that mental health data collections include CALD-relevant variables and that these are analysed to inform our understanding of mental health in immigrant and refugee communities and the impact of mental health services and suicide prevention programs in meeting the needs of CALD populations. It is particularly important to include a comprehensive list of CALD variables in all outcome data collections, and include reporting of outcomes for immigrant and refugee clients of mental health services as part of national reporting of service outcomes.

Applications to major Australian research funding organisations for funding of clinical or population mental health research can currently be made without reference to the cultural and linguistic diversity of the Australian population in the research design. Potential immigrant and refugee participants, particularly those who do not speak fluent English, can be and often are excluded from the research on the basis that inclusion is technically difficult and increases the cost of research. This perpetuates a culture of exclusion of immigrant and refugee communities from the Australian mental health research enterprise.

Engage major research funding organisations to develop consensus about the minimum CALD-relevant demographic variables that should be included in clinical and population mental health research studies and to develop strategies that will improve the level of inclusion of immigrant and refugee participants in Australian clinical and population mental health research.

We would suggest that implementation of these recommendations, which will require the joint efforts of many agencies and individuals will greatly contribute to the development of a culture of inclusion of all Australians in mental health research and evaluation and will enable the development of mental health policies, services and practices that will benefit all Australians.

Cultural pluralism confronts societies with a series of important challenges. These challenges include issues of distribution of resources; the legitimate role of government; and the purposes, structure and operations of social institutions, including health services.

The concept of equity in health is based on an ethical notion of fairness. Inequities in health arise when disparities in health status between two groups are considered avoidable, unacceptable, and unfair. Individuals should be able to attain their full health potential regardless of age, gender, race, or socio-economic circumstances.

Social justice and fundamental human rights lie at the heart of health equity. Inequities in health deserve our attention for both ethical and pragmatic reasons [156]. If it is the case that cultural minority groups are subject to systematic disadvantage as a result of social arrangements, including the conduct of mental health research and the organisation and delivery of mental health services, then a just society will change the social arrangements that result in such disadvantage.

The collection and analysis of health status data is central to moving toward equity in health. The disturbing absence of population-based mental health data concerning immigrant and refugee communities is in itself a great inequity in health. The dearth of mental health information about large segments of the population renders their health status and the possible deficiencies in performance of the mental health system invisible. Such problems must be brought to light to enable the development of strategies to reduce inequities in mental health status and in provision of effective mental health services.

Currently, in Australia, there exist major deficiencies in data and information on mental health status, mental health determinants, mental health service provision, and quality of service outcomes in immigrant and refugee communities. As a result it is difficult to set equity-oriented objectives and targets and to monitor and evaluate policy and service initiatives, or to estimate the personal, social and economic costs of doing nothing to rectify this situation or of interventions that will achieve policy objectives.

Although proposed actions are framed as recommendations they are not directed at specific agencies. The intent of the recommendations that have been made is to suggest strategies that will contribute to the development of a culture of inclusion of all Australians in the national mental health research enterprise. Commonwealth and State/Territory governments and many agencies and individual researchers will need to act if we are to collectively develop a culture of inclusion to ensure that Australian mental health research reflects the great cultural and linguistic diversity of the Australia population.

Mental Health in Multicultural Australia was commissioned by the National Mental Health Commission to carry out this study. We wish to express our gratitude to the Commission for providing funding to enable the study to be done.

We also wish to acknowledge the detailed and valuable reviews of earlier drafts of the report by the Australian Bureau of Statistics, the Australian Institute of Health and Welfare, the Commonwealth Department of Health and Ageing and the National Mental Health Commission. The report has benefited substantially from the comments made on earlier drafts by these organisations.

Mental Health in Multicultural Australia is a project funded by the Australian Government Department of Health.